|

|

|

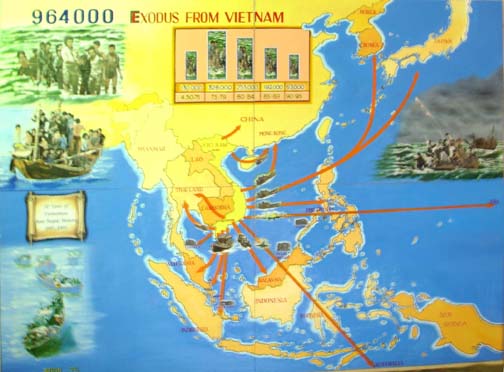

FROM WAR TO FREEDOM

by Commander Thong Ba Le, South Vietnamese Navy

I was sitting sadly by the wooden pier of the Naval Support Base with sorrows coursing through my mind. The disappointed feeling like waves upon waves undulating in my head. I felt uncomfortable with the wet uniform that stuck to my body. It was late in the afternoon, the sunlight pierced through dark gray clouds flowing to the far horizon. These clouds had produced a thunderstorm and heavy rain when they passed by this remote countryside early today. I kept breaking wild grasses with my fingers and threw them into the strong current of the river filled with broken lotus flowers and seaweed flowing to the sea. I did not notice that my hand started bleeding caused by the sharp edges of the grass. I did not even feel any pain because my heart was tormented by more agonizing situations that was happening to my country. I was disappointed in myself as a warrior and in the fact that I could not do any better to save my country from falling apart. I suffered a great deal by the circumstances around me, my eyes blurred with tears running down my cheeks. I hated everything that created or caused the problem and felt mentally weak. The whole thing could not be saved and was uncontrollable. I knew the collapse of this nation was not the fault of the patriots who vowed to defend it until they died. This morning I knelt in front of the flagpole at the Rung Sat Special Tactical Zone, among other soldiers pledging their oath. The bad news from the frontier of the northern part of central Vietnam were telling stories of the chagrined Commanding officers who fled their units before the advancement of the enemy. Many regiments, battalions of Army, Marine Corps, and Airborne were self-disengaged because their leaders were cowardly running away before the Communists’ attack. I exhaled sadly and avoided thinking about my children who were left behind in Hue city when the evacuation occurred over a month ago. Until now, I had no idea if they were still alive or dead. My duty as a senior officer did not allow me to leave my base and go to my hometown to pick up my four children who lived with their grand parents. Having to choose between my duty as a Naval officer and my responsibility as a father, I had chosen the first. I was spiritually pained as I accepted my decision as part of my honor. Because I became a career officer to defend my country, I had set my top priority for my job. "Country-Honor-Responsibility" was a fundamental part in the blood that essentially nourished my life. I was proud in recognizing that objectives in life were linked to this spiritual devotion. The wounds from the sharp grass were still dripping blood from my fingers; I continued to snap the wild grasses. My mind was drifting along with the muddy current of the Nha Be River. It was 6 o’clock in the evening, I heard in the distance, the battery sound of a 105-millimeter gun of the artillery friendly unit located in Cat Lai area. In the river, there were all kinds of boats and ships sailing toward Vung Tau, a coastal resort at the Soai Rap and Long Tao River mouth. As I walked toward the headquarters, a Non-commissioned officer saluted and handed to me a message from the Vietnamese Navy headquarters. I read carefully, signed the confidential instruction and returned it to the petty officer, then proceeded to the rear of the Naval base. The airplane runway located over there used to be an airfield for landing and take off for the U.S Advisors’ Cessna type aircraft. This airfield was not used any more since the U.S Navy transferred the base to the Vietnamese three years ago. At the end of the runway, near some warehouses, were two helicopters sitting lonely in the last sunrays of the day. The pilots, who flew out from Tan Son Nhat airport when this place was under heavy artillery bombardment by the North Vietnamese Communist, left them behind in the early morning. They stopped by this Naval base to request replenishment and refueling then continued their journey to the sea, perhaps flying to Con Son Island to regroup. I came close to the fences that surrounded the base and looked at the terrain. After reevaluating the defense system in this rear portion of the base, I decided to send two reconnaissance platoons to ambush the enemy; one platoon would spread out at the direction behind the civilians and one group at the riverside. While I watched, the wind blew from the river over the plain of wild tall grasses that created long green waves swelling to the other side of the field. Because mines were planned in this side of the field, I was confident that it would be costly for the enemy to attack the Naval Base from this direction. After carefully reevaluating the defense strategy and checking all fronts, I returned to the operation center and gave orders to the officer on duty of my decision to send two platoons out for the ambushed mission. It was getting dark and pigeons had returned to their nests on the roof of the warehouses. They snuggled each other while watching sailors walking in-groups below. Suddenly there were sounds of artillery echoing from Cat Lai. It was not the sound of friendly forces shooting 105-millimeters guns. Instead, it was the 122-millimeters rockets from the enemy that I heard so many times while commanding units at the DMZ. Almost every night I had to seek cover in the bunker when the Communists bombarded my base with this type of rocket. Then from the direction of Cat Lai Naval Base, I saw fire illuminating up a corner of the horizon and more and more gunshots were heard from the distance. I knew that the Naval base would soon be under heavy attack by the enemy. I quickly left the operation center and ran to the pier. When I got there, I saw many gunboats of the River Assault Group being deployed in the river toward Cat Lai. Farther in that direction, there were rubber boats teaming to my base with Navy personnel onboard. I recognized that they were UDT soldiers from the Seal Force. I waved to Commander H. whom I knew very well. We fought side by side in the northern front some years ago. We hugged each other when the boat reached alongside the pier. It was too long not to see a comrade-at-arms. My friend told me of the bad situation in Cat Lai and predicted that the defense of Naval base might collapse in a matter of an hour. After discussing and exchanging news about the whole figure of the battle, Commander H. requested refueling for his boats so his troop could have enough gasoline to reach Vung Tau. We shook hands firmly, Commander H. was so emotional when saying good-bye and good luck to me, and H. kept waving and looking back until the boat turned the curve of Long Tao River. My friend went to sea and I stayed to continue defending my post. I fell so heartbroken to see my friend leaving in such hurry. I talked to himself: "Perhaps this is the last time we see each other, wasn’t it? My friend, you have your belief and your own reason to leave, I do too. My situation and my idealism of "never give up the ship" is my reason. Besides, we have not fought yet, we ought to fight and fight to the last drop of blood. It was too sad, wasn’t it, my friend? There was over a million good soldiers, Navy, Army, and Air force who had fought the war fiercely and bravely all over the Motherland of Vietnam. Now, because of a few bad leaders who were cowardly and selfish, afraid of being killed, the power and the will to fight of the whole armed forces soon were disengaged before the attack of enemies. It was too sad, oh my Vietnam! Oh, Spirit of my Country! Oh all the Soul of the Ancestors and Heroes! I wanted very much to end my life, being overwhelmed with the feeling of shame of losing this battle. However, I contemplated that to die at this moment was to run away from my responsibility, instead of continuing to fight until I could no longer do so. Then if I died, I would be pleased and proud of having fulfilled my duty with the ancestors whom I hoped to see in the other world. The noisy sound from the headquarters brought me back from my thoughts. I hurried back to the flagpole area and gave the order to gather all personnel so I could inform them of the current situation. I made the announcement that whoever wished to accompany the Vietnamese Navy convoy to sail to sea were allowed to go immediately. The rest, who decided to stay and fight with me, would be sent to the defensive posts. I then dismissed my troop and was informed that only about one third of my sailors requested to leave. Two thirds had volunteered to continue to fight with their Commanding officer. I was so proud of these soldiers. I also ordered the release of all sailors who were being held in the military prison. I armed them so they could join their comrades-at-arms in defending their base. After I finished setting up the General Quarters, I was notified that the Vietnamese Navy Fleet was about to pass by the Naval Base, sailing in the direction of Vung Tau. I stood on the pier, watching small ships and big ships parading in front of me. There were hundreds of people on board, military personnel and civilians shouldered side by side from the stern to the bow, crowding on upper decks and lower decks. I felt pain in my stomach, so agonizing as though my guts were being cut out by a sharp knife; my intestines were being twisted up by an invisible rope. I stood quietly in the dark, witnessing the disappearance of the last ship in the convoy of South Vietnamese Navy Fleet. I tried to grasp my belief that was fading inside my soul, but it seemed hopeless. It was true that we were going to lose the fight, not in the battlefield but the enemy had won because our defense was self-disengaged. Then I remembered of my duty and responsibility to be ready for the coming task that I must face. I took a deep breath and walked sadly and slowly back to the operation center. I continued to communicate with friendly regional forces to coordinate the defense of the Rung Sat Special Zone against the future attack of enemy. The Master Chief petty officer informed me that there was a young officer to see me. I greeted my junior officer who worked under my command in Danang a long time ago. This young officer brought his ferrous cement junk boat from his Coastal Junk Force to convince his Commanding officer to leave the country. I thanked my young friend, smiled, and refused. We talked a little more then said goodbye. I wished the young officer well and walked him to the boat at the pier. The officer waved as his junk boat glided away to join his unit that was evacuating on Soai Rap River. The sky was filled with bright stars above, the crescent moon hung in the southern part of the dark sky, streaming pale beams from the universe. The end-of-spring wind from the river softly blew the dark mane of a 34-year-old man who looked older than his age. I had grown up through the war, witnessing and engaging in many historical events of my country, especially in the past few months. I was the witness of the changes of life in people who had reversed their belief to the point that I could not imagine and made me wonder so much of the perspective in life. When I arrived at the operation center, I was informed that it was calm on all fronts and the Regional force had three battalions scattering around Rung Sat Special Tactical zone. They had been under enemy rocket attack but without any serious damage. Based on my experience, I knew that the Communist would launch their attack after midnight and continue until 6 o’clock in the morning. They would have 6 hours to fight before dawn. As I predicted, it was about 11:45 PM when I heard the gunshots come closer from the direction of the Nha Be fuel depots. Then before a new day began, a 122-millimeter rocket, then a second, a third started falling everywhere and exploded when they hit targets in the base. The village located just outside of the Naval Base was hit and burned in vigorous flames. Two rockets fell onto two guarded posts and destroyed them. The enemy continued bombarding important locations of the base with rocket after rocket damaging the two helicopters, destroying the ammunition storage, the airfield runway, and warehouses. I led a platoon of sailors to re-enforce the defense of the rear front. We were running under the roar of rockets that were falling around. One sailor, just released from the prison, took off his helmet and handed it to his bareheaded Commanding officer. I thanked him but refused to take it. We continued on our route to the defended post near the fence. When we heard the terrible noise of rockets falling, we ducked on the ground, waited, then got up on our feet and ran again. From time to time, there were explosions so close that dirt and rocks covered our faces and heads. Normally it took about 10 minutes to travel from the operation center to this post; now it seemed like forever. Twenty minutes had passed but we had not yet reached the fence. Finally, we arrived at the post. This was a strong defended post with heavy armed artillery such as 12.7 millimeters machine guns, M79 grenade launchers, and communication equipment. From here, I could observe the whole area behind the base and toward the civilian village. I assessed and evaluated the situation here then decided to evacuate lightly injured personnel to the base hospital. The other posts reported the damage; beside the destruction caused by enemy rockets to warehouses, ammunition storage, only a few personnel were lightly injured, no fatal casualties were reported so far. The enemy only bombarded off and on and it seemed that they had not begun to launch ground attack. Perhaps they were waiting to regroup before sending their massive offensive attack or maybe they just wanted to scare the defender by bombarding them with rockets and destroying everything in the base as they did with other units in the Center of Vietnam. I predicted that the enemy would continue bombarding even heavier until daybreak. I radioed to the operation center and was notified by my officers that all units located in the Rung Sat Special Tactical Zone were also under enemy attack either by rockets or by ground forces. Some units suffered heavy casualties. One front was over-run and was trying to open an escape route toward the riverside. Enemy units, who were now moving along the riverbank and advancing to Nha Be fuel depot, occupied the Cat Lai Naval Base. Gunboats of the River Assault Group were shooting to stop the enemy with their naval firepower. There were a few boats being hit by B40, the Russian rocket launcher, and under fire. I decided to return to the Control and Command center with some sailors. While running across the airfield, at about 2 o’clock in the morning of April 30, 1975, I was surrounded by all kinds of gunshots and artillery sound. With explosions so loud, they reminded me of the 1968 Tet offensive event in Hue when I had to hide under ground for almost 28 days in the enemy controlled sector of the city. There were rockets falling around me while my mind was occupied with the previous experiences. The rockets fell and destroyed camps, houses and caused large fires everywhere. The fire engine and damaged control personnel were trying to extinguish as much as they could under the danger of being killed by falling rockets from the sky. Then at about 3 AM, there were rounds of rockets, one after another, precisely hitting important targets of my Naval Base as though being guided by the unknown internal artillery controller. I knew that the enemy had increased its pressure upon my defense. The left front reported being hit. They requested me to evacuate and withdraw. I complied with their request, but suddenly, all power was cut off. Lights went out, cable radios were interrupted, and communications between me and the units were terminated. Realizing that rockets had just destroyed the main generator house, I called all units from PRC-25 and ordered all hands to pull back and withdraw aboard boats that were ready at the pier to go out off shore. I then accompanied my staff members who carried maps and encoded materials and got aboard the Command and Control armed gunboat of the River Amphibious Group. The withdrawal to the boats under enemy gunfire and the embarking lasted about an hour without incident. My troupe then joined the naval units of the River Assault Group and deployed along the river to fight back enemy who were shooting from Thanh Tuy Ha side. Gunshots from big and small weapons were so noisy in the darkness of a cool night. Tracer bullets drew multiple tracks in all directions then exploded when they hit the unknown targets on both shoresof Nha Be River. Flares illuminated the sky like fireworks displayed in an official national holiday.

The sound from communicating radios mixing with the noisy gunshots, the yelling of crews of boats being hit by bullets had created a scene of war like one seen in a movie. The enemy was surprised to meet such a strong defense from the small units of courageous South Vietnamese Navy here, at the last eastern front. The battle continued until daybreak then slowly ceased; one could only hear a few wayward gunshots from the distance. The enemy finally stopped bombarding and they withdrew toward the direction of Thanh Tuy Ha ammunition depot. I radioed to the ambushed platoon leader who was still holding the front when all units withdrew at 0300 hours. The Ensign reported that the base was intact and the enemy did not send ground troops to attack the base. I informed the Commanding officer of the River Assault Group that I would return to the base with all personnel to re-group before the enemy could launch another round of attack. My command gunboat got alongside the pier in front of the Naval Base headquarters at 0700 hours on April 30, 1975. As the sunbeams pierced through the rosy clouds from the east, my crew disembarked ashore and prepared to go out to the defended posts again. Looking at the destruction of my base caused by enemy rockets, the fires in some warehouses, the collapsed roof and walls of the generator house, I knew that my base had suffered heavy damage. Nevertheless, I still believed that I could use all available means to continue to fight and to defend my Naval Base. I ordered my communication officer to destroy all unnecessary confidential and secret materials along with the equipment and coding machines. I then tried to communicate with Vietnamese Navy headquarters in Saigon for further instructions with the hope that it was still under command of a few senior officers who had decided to stay behind and fight as I did. After taking a quick tour around my base, I returned to the control center and was told that Saigon was in a panic and the Vietnamese Navy headquarters did not respond. I worried about what was happening there then ordered the supply officer to open the food warehouses to distribute rations, rice, and food to all retrieved units whose Commanding officers had left them and gone out to the sea to escape with others. Gunboats such as PBR's, Monitor's, LCM's, Scant Fom's etc., from different groups of the Riverine Force withdrew to my base and took refuge with me. At 10 am, while returning to the operation center, I suddenly heard running steps, noisy sounds of Hondas, Vespas, and motorcycles rushing to the main gate. Soldiers ran leaving behind their personal rifles and weapons all over the ground. I ordered them to stop to find out why they were deserting. They informed me that the radio reported that Saigon was in chaos, and their families were in danger. There was nothing for them to fight for and they requested permission to return home to their love ones. It was over. There was no one willing to fight because there was nothing for which to fight. The country was about to collapse under the Vietnamese Communists. Their Commanding officers as well as the leaders of the government had long gone abroad with their wives and their children aboard commercial airplanes or with the Vietnamese Navy Fleet. I was so desperate, angry, and upset in my heart. Soon, all others had gone and there were only a few sailors staying behind with me and the weapons that were scattered all over the cold ground of the Naval Base. I looked toward the blue sky while tears of despair were running down my face... The rain poured down when the fishing trawler was about to pass the intersection of Nha Be, Gia Dinh and Dong Nai on Saigon River. One branch of the river made a turn toward Cat Lai; the other one changed direction to the East Sea and later divided again into Long Tao and Soai Rap Rivers. The crowd consisted of people of all ages snuggled side by side under nylon tents, umbrellas, and raincoats to hide from the afternoon shower and strong wind blowing from the stern that helped to increase the speed of the big boat. Finally, the short rainstorm began to stop and the blue sky gradually appeared after the gray-dark clouds slowly drifted away to the west. The sunrays pierced through the clouds and sunshine returned over the Vietnamese refugees who evacuated from the fallen city of Saigon. From the direction of the Nha Be fuel depot, tens of South Vietnamese Navy gunboats were moving in a column formation. They were combat units of River Groups, Patrol Groups, or Special Mission Groups of the Navy Riverine Force. People aboard the fishing trawler were so surprised to see the gunboats with sailors in a state of combat heading toward Saigon. They wondered if the Commanding officer of the group was aware that Saigon had fallen and the North Vietnamese Communist now occupied the Republic of Vietnam’s Navy Headquarters. The South Vietnamese President, Duong Van Minh who came into office three days before, had surrendered to the Communists. It was about 1230 on April 30, 1975 and the refugees tried to signal to the sailors on these gunboats to turn around rather than continuing on to Saigon. Within the group of boats, I stood on the deck of the CCB gunboat, which continued to report to the South Vietnamese Navy in Saigon for further instructions, because I could not establish communications with the Senior officers at headquarters. Last night, the heavy attack of the enemy’s 122mm-rockets heavily damaged and almost destroyed my base. I decided to lead all gunboats whose Commanding officers had left their units in previous days to go abroad with their families. On the starboard side of the formation, I saw sailors taking off their flak jackets, navigating their small boats to follow big civilian ships, and trying to climb up the ropes to get aboard. They left their gunboats floating in the murky water of a historic river that witnessed the departure of the people from a defeated nation. The nurse from my base came up from below deck and told me that General Duong Van Minh had just surrendered to the North Vietnamese Communist. He ordered all units to drop their weapons and to stop fighting against the enemy of the people. I could not believe what she had just said. Tears began to flow down my cheeks, blurring my eyes. I felt disgraced by the leaders; they were violating and taking away by force the honor of a proud nation. I was outraged as to what was happening to us, the sailors, who did not want to give up our ship. Only cowards who were afraid of death made such decisions. We were not afraid, especially of dying for our country, for the cause of Freedom and Democracy. The Captain of the fishing trawler ordered his crew to a stop after navigating the vessel close to the Command and Control gunboat of his Navy friend. I saluted Captain C. when the two vessels got alongside. He told me about the bad situation in Saigon early this morning when he had to get underway in a hurry without a navigator aboard. Capt. C. was an engineering officer and had no experiences navigating the trawler out to sea. He also confirmed the surrender of President Duong Van Minh to the Communists. Finally, he asked if I would be able to help him and the people on board to navigate the vessel through the Long Tao-Soai Rap River and guide it to the open sea. I hesitated a moment, then radioed to the skippers of the gunboats. I informed them of what Captain C. had told me including his request for me to navigate his vessel, which was well guarded by hired special force soldiers. All my men advised me to take my family and get aboard the vessel to freedom; they would follow me after getting their own families. I felt conflicting emotions raising up inside of me as I sincerely thanked my comrades-at-arms that had fought valiantly during the enemy attack the previous night. I also apologized for not remaining with them until the end of this heartbreaking chapter in our nation’s history. After saying good-bye and wishing one another good luck, we separated in opposite directions. I helped my wife, Minh, and our four young children to climb aboard the trawler while my comrades-at-arms continued their journey to the unknown future. I took the second in command and began to navigate the 300+ ton vessel with more than 200 people aboard including a Chinese-Vietnamese from Cho Lon district who bought this modified fishing trawler to escape for freedom... We passed the Nha Be oil depot when the fire smoke from the Naval Support Base at Nha Be was still hanging thickly in the sky. I stopped the engines to recover my personnel from the base. Many of them decided to stay behind for different reasons. Some said that they had planned to find a way to the sea after they found their families. The Chinese and other passengers got all the Vietnamese “dong-piasters” that were no longer valuable to the refugees. The sailors gave them bags of rice and instant noodles. They said good-bye and good luck to one another, people whom had never met each other before and would never meet again in their lifetime. Before they left, the sailors also told me that Viet Cong ambushed a merchant ship, Viet Nam Thuong Tin, on the Long Tao River, about half an hour ago at 1330. They shot rockets and killed many passengers aboard; among them was Mr. Chu Tu, one of the South Vietnamese famous writers. Having heard this, Captain C. and I decided to navigate the trawler through Soai Rap River instead of Long Tao River. Although it was more difficult to navigate through this shallow but wide river, it was also easy to observe and to avoid being hit by Communist B-40s set up ashore. One of the gunboat skippers gave us an Army map of the Vung Tau, Soai Rap area, and a few navigation aids. I needed those tools to help me fix and determine the position of the vessel because all I had before was a magnetic compass. We got underway again at approximately 1415 hours and proceeded to the Soai Rap River, following the wake of the boats cruising ahead. There were all kinds of boats and vessels heading toward Vung Tau harbor. I saw many Landing Craft Utility (LCU) boats of the Army Transport Corps, several Landing Craft Mechanized (LCM), Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP), and a few Patrol River Boats (PBR's) of the South Vietnamese Navy. I also glimpsed civilian junk boats, vessels, and others steaming at their maximum speed. The whole country was still upset and confused from losing their beloved homeland. The people were in a panic when they heard about the advancement of the North Vietnamese Communist toward the capital of the Republic of South Vietnam. They tried to find any seaworthy means to escape the dictatorship regime of the Communists. The afternoon breeze blew softly from rows of low water palm trees on the riverbanks. The surface seemed to light up under the late afternoon sunshine, blinking with thousands of small imaginary stars reflected from the calm surface. A few long-necked cranes spread their wide wings, their shapes reflected in the smooth surface while sea birds slowly flew above the reeds along both sides of the river. Nature seemed to ignore the changing hand of a nation. It appeared normal to the eyes of the evacuees who already were aware of the events that caused them to leave behind their livelihood including their birth places, tombs of their ancestors, and their beloved ones. They also knew that anything that happened to them on this journey of destiny could affect their future. They were the refugees who escaped from communism to seek freedom for themselves and their families. The fishing trawler continued its voyage to an unknown destination at sea. I reduced the speed to be safe in an unpredictable current over the varying depths of the Soai Rap River. We stopped our vessel from time to time and recovered people of all ages and from all classes of society from their small boats that were overloaded and sinking. The number of passengers increased when I saw the hilly sites of Vung Tau harbor with its white lighthouse on top the highest mountain. From time to time, helicopters from the lost SVN Air Force headed to the open sea toward the designated positions of the US Seventh Fleet waiting to receive South Vietnamese evacuees from the fallen capital city. From the direction of the Cat Lo Naval Support Base, several vessels including LCU's, LCM's, and all kinds of gunboats and junk boats were hurriedly heading to the East Sea. Hundreds of small boats also rushed out from the Cuu Long (Mekong) River. Navy boats of the 4th Riverine Force followed fishing trawlers, merchant ships, or Navy ships to request permission to aboard because their gunboats were not sea-going vessels. We stopped our trawler to rescue many passengers from sinking boats. As the sun was setting, we passed Vung Tau harbor. I maneuvered the vessel out of the channel and changed course toward the southeast. In order to get a possible fix on the ship, I used the old magnetic compass to get the bearing from Vung Tau’s lighthouse and used chopsticks to measure the distance on the map. We did not have navigation aids aboard. Captain C. said that in the last minute, the navigator who kept all navigating tools could not make it to the fishing trawler. The crowded evacuees found room where they could. Some were seated, others standing side by side on the front deck, upper deck or lying next to the small conning station. There was no place to go and no room to move around. According to Capt. C., the number of passengers was approximately 400 compared to about 200 when the vessel stopped at Nha Be Naval Support Base at 1400 hours this afternoon. He also told me that in their rush to leave Saigon, they were short on diesel fuel. We needed to find a supply source to replenish the fuel in order to reach the US War ships of the Seventh Fleet in the open sea. The sun had set behind the range of dark green trees ashore from the northwest, behind the lonely vessel heading eastward. The evening stars began to show their blinking lights in the purple petals of the universe. The long waves rolled toward the far away shoreline, one after another they rocked the boat back a forth comforting the Vietnamese refugees. Light rays from the Vung Tau lighthouse frequently pierced the dark night with their bright streams. It was almost 2200 hours when the vessel drifted from Vung Tau. Beside the noisy sound of the engines and the whisper of the sea, the people were so quiet. They were deep in the thought of being on the exodus much like the people of Israel were looking for their land long ago. They kept their hope although they realized that the chance of being rescued in the East Sea was as likely as finding water in the desert. They would let destiny guide their lives and wait for the uncertainty of luck. The evacuees were awakened by loud voices from the bridge. The person on watch reported to Capt. C. and me that there was a merchant ship about one nautical mile on the port side of our vessel. We maneuvered toward the big ship. When we were closer, Capt. C. used a loud speaker to talk with the Captain of the ship. Captain C. requested permission for everybody to get aboard the merchant ship. It was a South Korean vessel with homeport in Seoul. Its Captain, who spoke fluent English, denied our request because he did not have the authority to let people board. He sadly explained to us that because the fall of South Vietnam happened too quickly, his country as well as his Maritime Company did not yet have a policy or procedures in place to deal with the situation in Vietnam. Politics and national interests prevented them from reacting; the Republic of South Korea did not yet give orders to rescue Vietnamese refugees at sea. The words from this Captain confirmed the abandonment of Vietnam of a previous allied country that had fought side by side to stop the aggression of the International Communist Party-Russia, China, and North Vietnam. The ideals of the Free World Community for Freedom and Democracy to all nations were limited to those who had the power to defend themselves against the Red Communists. When the time came, the weaker was the loser to the dictatorship because the Free World Community turned their back and refused to help due to their own interests. I was angry at that thought and was very upset with myself for having devoted my whole life for the ideals that I believed. Many times, I was almost killed in combat, at the sea, north of seventeenth parallels or in the jungles near the Viet Cong secret zones at Quang Nam Province. Last night, I defended my base until the last minute of the unwanted war. Now, in the dark cool night in the middle of the East Sea, I found the first lesson of the truth. Everything was politics and for national interests, not for ideals or freedom fighters at all. The South Korean Captain said a few nice words to comfort the evacuees then he changed course to north-northwest toward the direction of Hai Nam Island with engines all ahead full, and left the scene. He left behind, in the darkness of the night, 400 Vietnamese refugees aboard a small trawler that was running out of diesel fuel, drifting on the waves to find sources of oil from abandoned vessels in the mighty Pacific Ocean. The clear sky on the first night in May 1975 was decorated with bright stars and a crescent moon in the western sky. Its pale streams could not light up this “Journey of Destiny” of desperate refugees aboard all types of seaworthy vessels heading toward the direction of the sunrise hoping that the US Navy War ships at sea would rescue them. The fishing trawler changed course 90 degrees, heading to the area where I saw many boats and vessels of the RVN Army rushing out to the east. We were about to reach that location after slowly zigzagging to look for abandoned LCUs floating in the water. The crescent moon still hung in the starry sky above the starboard side of the ship. A dark shadow appeared like a phantom rocking with the waves. The observer realized that it was a Landing Craft Utility and reported it to Captain C. The Captain ordered the engineering NCO below to stop the engines. I carefully navigated the trawler alongside the ghost landing craft. There were no living creatures aboard the vessel except pieces of luggage, clothing, shoes and food scattered all over the main deck. It was so dark, no emergency lights of any kind. It seemed that the refugees left in a hurry to board floating pontoons or larger ships. Captain C. gave the order to the young people to form a line from the trawler to the diesel tank of the LCU. Under the search light from the bridge, the group scooped oil from the tank with buckets and passed them along the line to dump into the fuel reservoir of the trawler. The task progressed smoothly under the pale moonbeams in the direction of our homeland. In the cool quiet night, aboard an abandoned ship somewhere in the East Sea, these people shared a common goal, and it was the determination to survive under difficult situations. The will to stay alive so they would be rescued was so strong among strangers who never knew one another before the tragic event of their country. They joined hands with one another and leaned against each other for support. While their men passed buckets of diesel fuel along the human line, their spouses shared goods with one another on the front deck of the trawler. The Chinese had brought silk fabric, valuable clothes, and other things with them. They gave homemade pajamas and sleepers to everyone aboard. The humanity between people who had never met before warmed the hearts of the evacuees. It was about 0400 hours on May 1, 1975. They had completed the mission of getting diesel fuel and the young men began to move barrels of fresh water from the main desk of the LCU to the upper deck of the fishing trawler. Once it was done, I maneuvered the ship out from the abandoned floating landing craft, and resumed course eastward with more speed than before. The LCU was seen undulating on top of the waves, rolling away and disappearing in the darkness of the night to an unknown destination. In the horizon, the first light of dawn began to color the clouds drifting across the sky. It was past 0500 hours and even the cool ocean breeze could not comfort the sleepless people. Then the sun appeared slowly from below the pink horizon. Its sunrays created a multi-color shrine over the ocean, like a stream of gold spreading on a blue carpet. The gold dusts in the air were blinking toward the depths of the boundless universe. From the starboard side of the trawler, the refugees soon spotted the shuttle shape of a US Destroyer. Everybody yelled and jumped on their feet. It seemed that life had returned to the desperate evacuees. The atmosphere changed, people started talking to each other, and some even prepared their belongings as to get ready to board the war ship. A few refugees prayed; others waived to the ship with towels, blankets, and clothes to get attention of the crew members of the war ship. When I navigated the vessel closer, I noticed that there were many boats, junk boats, fishing vessels, and sailboats surrounding the US ship but none was permitted near the Destroyer. As soon as I moved the trawler a little closer, sailors aboard the war ship started shooting their M-16 rifles into the sky to chase us away. Everybody was surprised and disappointed. They wondered what was going on, and then they all became very upset. The United States Navy refused to assist the Vietnamese refugees and chased them away? Did the people of Saigon not say before April 30 that the US Seventh Fleet would wait in the open sea to help the evacuees? Did the Unites States government order their war ships not allow the refugees? There were questions after questions that worried the poor people who snuggled like sardines aboard the small vessels. They wondered what would happen to them and their families if the US ships did not rescue them at sea. They became angry and started yelling at the unsympathetic sailors on the war ship. Then from nowhere, vessels of all kinds approached the scene and suddenly I saw that the US Destroyer was changing course, increasing speed, and heading to the southeast. She left behind her, traces of white water pushing from propellers and tens of boats, trawlers, and junks with crying human beings aboard. Sorrow returned in my heart when I thought about the actions of this allied country, of the foreign policy that her leaders had followed and implemented in Vietnam. They sent hundreds of thousand US soldiers to fight in an unconventional and limited war in a country smaller than California. More than fifty-eight thousand brave young men from the US, died in the deep jungles of the Truong Son Mountains. Their dead bodies floated in the muddy water of the Mekong River and their flesh and bones scattered over the ground of a poor and corrupted country. Then the politicians decided to withdraw the US forces and abandon the Vietnamese soldiers, who had fought for freedom and democracy. They wanted to end the costly war and to “save face.” The sun had risen to the zenith; the warm air of the tropical East Sea bothered the crowded and sweating refugees. After a while, Captain C. decided to change course and resume speed toward the international maritime route hoping that we would be able to meet merchant ships from other nations that might rescue us. When the vessel got closer to our trawler, a young Navy Lieutenant Junior Grade who was the skipper of the small patrol craft, requested permission to board with three members of his crew. He told Captain C. that his 3000-gallon fuel tank was still mostly full and if the trawler towed his boat, it would become a reserved asset for the trawler. We agreed and passed the line down to his crew and towed the PCF behind the stern. The fishing trawler continued under the heat of the tropical sun. Onboard, refugees used nylon sheets, blankets, and towels to cover against the penetrating sun. Suddenly, everybody heard the coughing sound of the engines. Then it became quiet. Captain C. rushed down to the engine room and later came up to tell everybody that water was mixing with the diesel oil that the refugees obtained from the LCU the night before. It would take a couple of hours to clean up before the engines would run again. It was another piece of bad news for the dejected evacuees who began to realize the uncertainty of the journey for freedom that they had chosen. Twice they were refused rescue by the ships of two previously allied countries. It was now at 1500 hours on the second day of the trip that they still had not seen any other vessels in the radius of their position in the Pacific Ocean. As their ship drifted on the East Sea, at least Mother Nature seemed kind to them by letting the sea remain calm during the past few days. Thanks to the good weather and smooth sailing, the people did not get seasick and were not too tired. About two hours later, the people aboard felt relief when they heard the sound of the engines starting. The ship began to move again toward the horizon. I made an estimated fix on the map then asked Captain C. to release me for a while so I could visit my family. I had not seen them since the departure of the trawler from the Nha Be Naval Support Base. Before I left the bridge, I looked through the binoculars in all directions. First, I saw nothing on the port side. As I moved to my right looking forward to starboard side, I spotted a trace of light smoke from the dark blue horizon. My instincts told me that it would be the smoke coming out from the exhausted turrets of a seagoing vessel. Captain C. also had seen the smoke and he ordered the skipper of the Swift boat that could run up to the speed of 25 knots, to prepare to intercept the unknown target and request their assistance. We knew that the fishing trawler would not be able to catch up with the other ship because of her slow speed. A Lieutenant Commander who spoke fluent English accompanied the four men crews on this hopeful mission. They used rubber tires to cover the 81mm mortar and other 50 caliber machine guns of the gunboat to avoid any misunderstandings of being an attack boat. They also hoisted a Red Cross flag on the flagpole to show the sign of SOS. All eyes followed the patrol craft as it increased speed and prayed for the hope of being rescued. The shape of the Swift boat then disappeared on the rolling waves, leaving behind questioning faces onboard the lonely fishing trawler that slowly followed the direction of the light cloud of smoke. Finally, over half an hour later, the refugees stood up on their tired feet and jumped up and down with joy. In front of them, the big US ship rolled in the waves and waited for the trawler. Beside the war ship, under the word AO, there was the PCF pitching slowly in the water. I moved to the bow of the fishing trawler between the wall of happy people who pressed against one another to make way for me. Some patted my back to thank me and congratulated me on my navigation skills that brought them to freedom. I humbly thanked them and proceeded slowly toward the ladder leading to the front deck. On the front deck, I used a hand loudspeaker and expressed our gratitude to the Captain and crew of the Fleet Oiler that had stopped and rescued over 400 refugees onboard this vessel. I requested permission for us to board the ship because of the unsafe conditions on the trawler. The Executive Officer of the ship relayed the message from the Captain that the ship could not allow refugees to come aboard because of security of the Oiler. However, the Captain already received the approval from his Chain of Command to tow this small vessel with all refugees onboard to the Seventh Fleet station at sea. When I reported the conversation to Captain C., he announced the good news on the loudspeaker. The crowd broke out a roar of joy. People hugged each other; tears of joy immediately ran down their sunburned cheeks. Everybody now knew it was true that the United States Navy had been waiting at sea, outside the Vietnam water territory to rescue evacuees from the fallen country. They were also sure that the Journey of Destiny to Freedom was about to reach its destination. The Lord had protected and guided his people who did not want to live under the dictatorship of the North Vietnamese Communist. The universe began to drop its velvet petals over the vast ocean; stars were blinking above the big ship with a small vessel towed behind. The evening sea breeze cooled off the heat of the East Sea and comforted the happy refugees. They smiled and talked to each other about the future, some had already planned what they would do when they reached the land of opportunity in the Far West. Then the chef of the US War ship served dinner to all the evacuees. Plates of hot rice, bean sprouts cooked in eggs and pork, fresh milk, bananas, apples, and oranges were passed down from the stern of the Oiler to hungry refugees. During the last two days, they had only consumed instant noodles and condensed milk. While enjoying the hot meal with my family, I tried not to think about the well-prepared rescued plans of our friend, the United States of America. They had thought of everything including bean sprouts and fat pork meat to serve the Vietnamese evacuees. What else should not we know of the whole picture of the falling of Saigon? The plan to rescue hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese refugees in the first three days of May 1975 was a huge and well-organized rescue effort. With hundred of ships and helicopters, and numerous agencies within all branches of the US Arms Forces and government, America had shown the determination to accept their responsibility to deal with the Vietnamese refugees fleeing from their lost country. On the early morning in May 2, 1975, my family and I stepped onto the ramp of the Landing Ship Tank USS Barbour County-LST 1195 with 400 other refugees from the fishing trawler. I looked back to see the abandoned fishing trawler for the last time as it slowly drifted away with the undulating waves. The trawler that I had helped to command since the afternoon of April 30, 1975 had carried my family and me to Freedom. I felt like losing a good friend. Turning around as I carried my daughter, I then walked along with my family, behind the line of refugees to the checkpoint inside the lower deck of the ship. Without further delay and according to plan, the Barbour County got underway at 1500 hours May 2, 1975, on the first birthday of my youngest son, Le Ba Phuc. There were hundreds of Vietnamese evacuees aboard the big ship, lying on the deck in the huge belly of the tank carrier. The people enjoyed three hot nutritional meals a day. Breakfast consisted of omelets, cereals, fresh milk, and fruits. Lunch included hot dogs, hamburgers, French fries, and cakes. In the evening, people received rice, meat, vegetables, bean sprouts, and ice cream for dessert. The time went by, everyday the refugees ate their meals then tried to get some sleep. In the early morning of May 6, 1975, the Landing Ship Tank USS Barbour County-LST 1195 reached the Philippines water territory. From the distance, the people saw the greenish mountain range on which the famous resort, Baguio City was located. The morning fog still covered the blue ocean when the ship dropped its anchor in Subic Bay and all Vietnamese refugees were told to get ready for the transfer ashore by small landing crafts. The Captain of the USS Barbour County said a few words of best wishes to the refugees then we began to load ourselves onto small boats that got along side the LST. I stood barefoot on the hot deck of the small landing craft heading to the pier inside the bay. Tears blurred my eyes as I looked at the American flag flying in the wind blowing from the sea. It was the same Stars and Stripes flag that I saw every morning adjacent to the Yellow with Three Red Stripes South Vietnamese flag on the flagpole of the Coastal Security Service in Danang 10 years ago. I served for three years as Captain of Patrol Torpedo Fast (PTF) in the Maritime Special Operation Force. This time, I felt in my spirit that this seemed like a different flag. I did not know from where this feeling came. Perhaps the Journey of Destiny was the destiny for not only the 400 evacuees onboard the fishing trawler, but it would be one of the Journeys of Destiny of my poor Mother land. Millions of young innocent, patriotic nationalists and courageous soldiers died to protect those flags and sacrificed their lives for the cause of Freedom and Democracy for their homeland. Were those sacrifices in vain? The cool ocean breeze could not comfort the wave of sorrows in the heart of this Vietnamese refugee. In less than seven days, destiny had changed the life of a proud South Vietnamese Navy Officer into an unwanted political asylum seeking refugee. The man had just lost his beloved country that he had fought and defended all his life and was about to face new challenges of struggling to survive in an unknown world.

(***)To CDR H.B. Le, United States Navy, Commanding Officer USS Lassen, DDG82 Commanding Officer USS Lassen (DDG-82) FPO AP 96671-1299 November 6, 2009 Dear Captain, Congratulations on your command. I read with interest the press release about your visit to your homeland. I was the Executive Officer of the USS Barbour County (LST 1195) at the time of your rescue. I have wondered throughout the years what became of the myriad people we took on board and transported to the Philippines (Grandy Island). Again, congratulations and enjoy your tour.

Sincerely,  About The Author

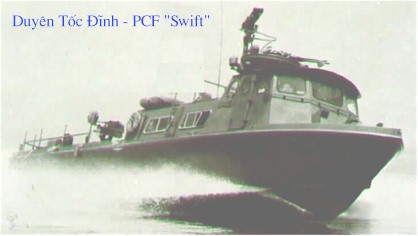

In 1965, he abandoned the safety of serving on a ship at sea and volunteered to join the Coastal Security Service (CSS), a covert special naval operations unit of the Strategic specialists conducting covert operations north of the 17th parallel. There, he was appointed as Captain of PTF-6 which was a new and modern Patrol Torpedo Fast (PTF) at the time.

He continued to serve in the Coastal Security Service until he was appointed Commander of Task Group "Sea Tiger" operating in the Cua Dai, Thu Bon river, Hoi An. It was a very heavy and dangerous task because they were required to use small gunboats to patrol and protect many waterways controlled by the enemy. In 1970, he served as commanding officer of Da Nang naval base. In 1972, he was appointed Deputy Commandant of the Military Instruction Directory of the National Military Academy in Dalat. This position was particularly important in the training of cadets to become great leaders of the nation in the future. As a naval officer, he held a military position normally assigned to army officers, at the military college known as Dalat Army Military Academy; he showed great talent and an especially high capacity for this job. He then held many key positions such as Deputy Chief of Staff of Operations at the Sea Operations Command in Cam Ranh bay; Commanding Officer 32nd Coastal Assault Group in Hue ; Commanding Officer Cua Viet Naval Base; Commander Task Group 231.1 in Thuan An. He fought until the last minutes in Nha Be Naval Support Base, his last unit at which he served as Deputy Commander (acting Commanding Officer). He escaped with his family to the United States on the afternoon of April 30, 1975.

|

The watchman reported to us that he had spotted on the port side, about five nautical miles, a high-speed vessel heading to our position. I looked through the binoculars and noticed it was a Swift boat. Perhaps this Patrol Craft Fast (PCF) was under the command of the Third Coastal Patrol Force, stationed at Vung Tau.

The watchman reported to us that he had spotted on the port side, about five nautical miles, a high-speed vessel heading to our position. I looked through the binoculars and noticed it was a Swift boat. Perhaps this Patrol Craft Fast (PCF) was under the command of the Third Coastal Patrol Force, stationed at Vung Tau.

Vietnam Refugee Becomes U.S. Navy Captain

Vietnam Refugee Becomes U.S. Navy Captain